Insomni'hack 2024 CTF Teaser - Cache Cache

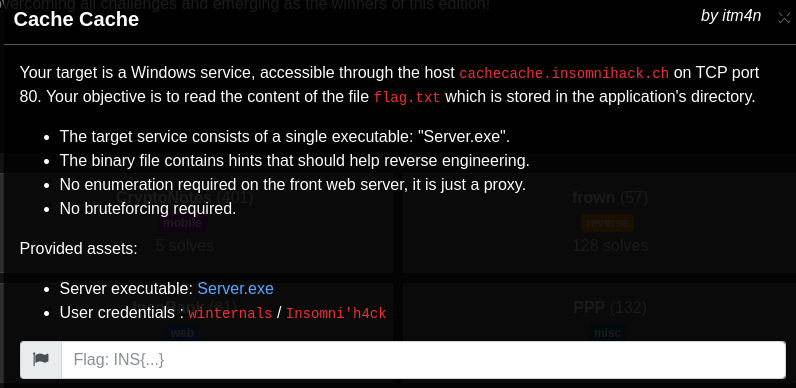

Last year, for the Insomni’hack 2023 CTF Teaser, I created a challenge based on a logic bug in a Windows RPC server. I was pleased with the result, so I renewed the experience. Besides, I already knew what type of bug to tackle for this new edition. ![]()

Personal thoughts

Like my previous write-up, I will begin with some thoughts about the difficulties of creating a challenge and facing inevitable criticism.

This CTF has become so notorious over the years that creating a challenge for it is a big responsibility, and also a challenge in itself. Ideally, we want to come up with original ideas, and somehow implement them within a limited time without making mistakes that would result in unintended solves. In a perfect world, this should result in something that is difficult enough for the most experienced teams, but does not leave beginners behind. No need to say, it is a very delicate balance to find.

One of the consequences is that it is virtually impossible to please everyone. And the harder the challenge is, the more likely you are to face frustrated players, amongst which some will definitely let you know about their feelings.

Throughout the event, I received two complaints remarks. The first one was that the teams who had previously worked on (or even solved) my previous challenge had a huge advantage, compared to other teams who had to start from scratch, and figure out how to communicate with the remote server. In the same vein, some other players asked why a skeleton code snippet for the RPC client initialization was not provided, at least to get people started.

My answer to that is relatively simple. Since I had already published a detailed write-up for the previous challenge, I thought it would provide a sufficient head start that would offset the initial difficulty for the teams that were new to those concepts. On top of that, in addition to the reverse engineering methodology, it provided code snippets that showed precisely how to connect to the server. All it required was a quick search. With keywords such as “windows rpc ctf”, which are not even that specific, my blog post is the 7th result (at the time of writing).

Google search with the keywords “windows rpc ctf”

Google search with the keywords “windows rpc ctf”

Write-up

The challenge

The description of the challenge is similar to the previous one. The target is a Windows service that we can reach through port 80. The server’s executable is provided so that players can reverse it and test it offline.

Initial analysis

I won’t go into the details of how to reverse engineer the server as I already did that in the previous write-up. The methodology is exactly the same. The first goal was to reconstruct the IDL file. Below is the original file I extracted from the sources of the project.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

[

uuid (9b5cb5a7-624d-4ae2-ab79-529fbb2f3072),

version(1.0),

pointer_default(unique)

]

interface winternals3

{

typedef struct _PLAYER_CONTEXT

{

wchar_t wszPlayerName[64];

wchar_t wszPlayerLocation[64];

int bPlayerFound;

} PLAYER_CONTEXT, * PPLAYER_CONTEXT;

typedef [context_handle] void* PCONTEXT_HANDLE_TYPE;

long HsCreatePlayer([in] handle_t binding_h, [out] PCONTEXT_HANDLE_TYPE* pphContext, [in, string] wchar_t* pwszName); // 0

long HsGetPlayerName([in] handle_t binding_h, [in] PCONTEXT_HANDLE_TYPE phContext, [out, string][ref] wchar_t** ppwszName); // 1

long HsCallReady([in] handle_t binding_h, [in, string] wchar_t* pwszMessage, [out, string][ref] wchar_t** ppwszResponse); // 2

long HsHidePlayer([in] handle_t binding_h, [in] PCONTEXT_HANDLE_TYPE phContext, [in, string] wchar_t* pwszLocation); // 3

long HsGetPlayerLocation([in] handle_t binding_h, [in] PCONTEXT_HANDLE_TYPE phContext, [out, string][ref] wchar_t** ppwszLocation); // 4

long HsSeekPlayer([in] handle_t binding_h, [in] PCONTEXT_HANDLE_TYPE phContext); // 5

long HsGetFlag([in] handle_t binding_h, [in] PCONTEXT_HANDLE_TYPE phContext, [out, string][ref] wchar_t** ppwszFlag); // 6

long HsClose([in] handle_t binding_h, [in, out] PCONTEXT_HANDLE_TYPE* pphContext); // 7

}

Through reverse engineering, you should have found a similar result, without the names of the two custom types and the function parameters. The procedure names were provided in log messages.

First contact

From there, if you tried to invoke any of the procedures, there is a chance you got only “Access Denied” errors. If so, you probably missed a key aspect of this RPC server.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

// ...

Log(L"INIT > Registering protocol sequence: %ws:%ws\r\n");

RVar1 = RpcServerUseProtseqEpW(

(RPC_WSTR)L"ncacn_http", 10, (RPC_WSTR)L"8000", (void *)0x0

);

if (RVar1 == 0) {

Log(L"INIT > Registering authentication information\r\n");

RVar1 = RpcServerRegisterAuthInfoW(

(RPC_WSTR)0x0, 10, (RPC_AUTH_KEY_RETRIEVAL_FN)0x0, (void *)0x0

);

if (RVar1 == 0) {

Log(L"INIT > Registering interface\r\n");

RVar1 = RpcServerRegisterIf2(

&winternals3___RpcServerInterface, // RPC_IF_HANDLE IfSpec

(UUID *)0x0, // UUID *MgrTypeUuid

(void *)0x0, // RPC_MGR_EPV *MgrEpv

0, // unsigned int Flags

0x4d2, // unsigned int MaxCalls

0xffffffff, // unsigned int MaxRpcSize

ServerSecurityCallback // RPC_IF_CALLBACK_FN *IfCallbackFn

);

// ...

Note that, in my case, Ghidra automatically imported the PDB file. That’s why some symbols are shown here, but it was possible to guess them.

The thing to notice here was that the last argument of RpcServerRegisterIf2 is not null, which means that a security-callback function is implemented. In the documentation, you can read that “specifying a security-callback function allows the server application to restrict access to its interfaces on an individual client basis”.

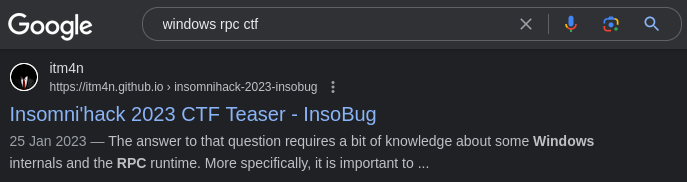

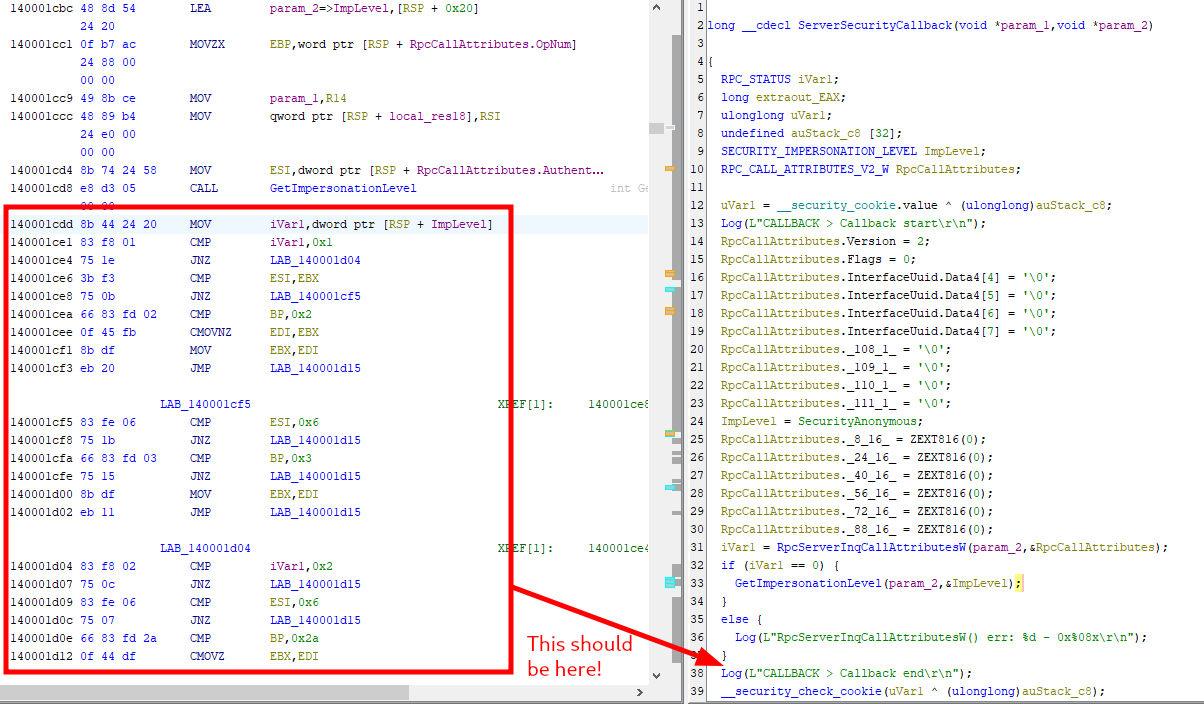

Now, I have no idea why, but if you relied on the pseudo-code generated by Ghidra, you would have been out of luck because it does not show the most important part of the function, as highlighted on the screenshot below. This was not intentional from my part.

Analysis of the security callback with Ghidra

Analysis of the security callback with Ghidra

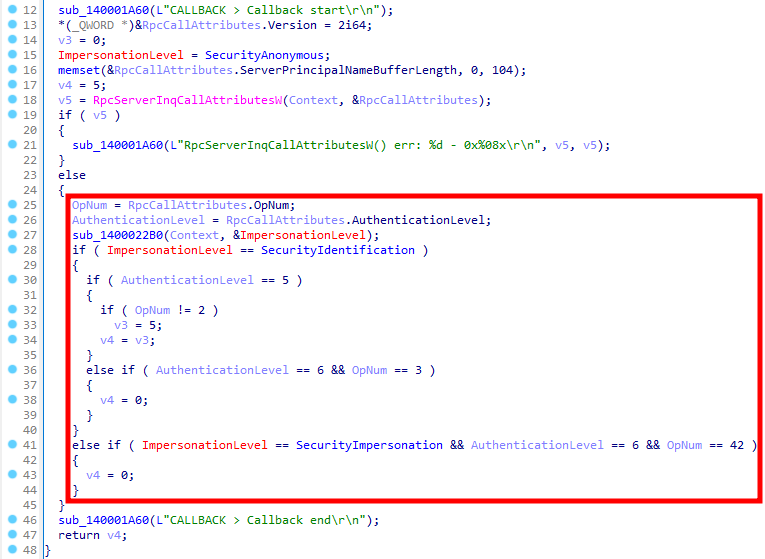

IDA, on the other hand, does a way better job with it. It was able to generate a pseudo-code that is very close to the source, even with the free version I used for this next screenshot.

Analysis of the security callback with IDA Free

Analysis of the security callback with IDA Free

For the comparison, below is the original source code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

RPC_STATUS ServerSecurityCallback(RPC_IF_HANDLE InterfaceUuid, void* Context)

{

Log(L"CALLBACK > Callback start\r\n");

RPC_STATUS status = E_UNEXPECTED, authorization = RPC_S_ACCESS_DENIED;

RPC_CALL_ATTRIBUTES_V2_W RpcCallAttributes;

USHORT opnum;

DWORD al;

SECURITY_IMPERSONATION_LEVEL il = SecurityAnonymous;

ZeroMemory(&RpcCallAttributes, sizeof(RpcCallAttributes));

RpcCallAttributes.Version = 2;

RpcCallAttributes.Flags = 0;

status = RpcServerInqCallAttributesW(Context, &RpcCallAttributes);

if (status != RPC_S_OK) {

Log(L"RpcServerInqCallAttributesW() err: %d - 0x%08x\r\n", status, status);

goto cleanup;

}

opnum = RpcCallAttributes.OpNum;

al = RpcCallAttributes.AuthenticationLevel;

GetImpersonationLevel(Context, &il);

if (il == SecurityIdentification) {

if (al == RPC_C_AUTHN_LEVEL_PKT_INTEGRITY) {

if (opnum == 2) { // HsCallReady

authorization = RPC_S_OK;

}

} else if (al == RPC_C_AUTHN_LEVEL_PKT_PRIVACY) {

if (opnum == 3) { // HsSeekPlayer

authorization = RPC_S_OK;

}

}

} else if (il == SecurityImpersonation) {

if (al == RPC_C_AUTHN_LEVEL_PKT_PRIVACY) {

if (opnum == 42) {

authorization = RPC_S_OK;

}

}

}

cleanup:

Log(L"CALLBACK > Callback end\r\n");

return authorization;

}

Anyway, what you had to figure out is that the security callback function takes a decision as to whether it should authorize a client’s call based on three pieces of information:

- the

OpNumof the procedure invoked by the client; - the Authentication Level associated to the client’s binding;

- the Impersonation Level associated to the client’s binding.

For instance, authorization would be granted for the procedure with the OpNum 2 (HsCallReady) only if the impersonation level is SecurityIdentification and the authentication level is PKT_INTEGRITY, which are two parameters a client can set when initializing its binding handle. Other similar checks are performed when invoking the procedures with the OpNum 3 and 42. If you try to invoke other procedures, the function will always return RPC_S_ACCESS_DENIED.

Now, if you analyzed all the procedures, you should have found that they pretty much all need to be invoked, with the appropriate values, in order to obtain the proper server-side context that will allow you to eventually get the flag. But, as we’ve seen, some of those procedures are unreachable because of the security callback. At this point, your conclusion should be that the problem is impossible to solve. Unless there is a trick…

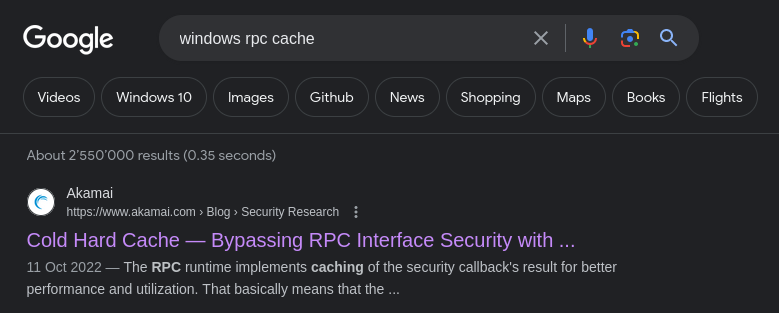

A caching issue

Of course, there was a trick! The name of the challenge was supposed to hint towards the solution. With a quick search including the keywords “windows rpc cache”, the very first result should have been this one (at least at the time of writing).

Google search with the keywords “windows rpc cache”

Google search with the keywords “windows rpc cache”

In the blog post Cold Hard Cache - Bypassing RPC Interface Security with Cache Abuse, Ben Barnea and Stiv Kupchik discussed a very interesting topic I wasn’t aware of before this publication. Essentially, they explain that the result of a security callback can be cached, either per interface, or per call, which can lead to tricky logic bugs if not handled correctly by the developers.

Let’s say we have an RPC server with one interface and two procedures A and B. This server wants to grant access to low-privileged users to procedure A, but not B, using a security callback. If a client connects to the server and invokes A, the request is served. However, if the same client connects and invokes B, the access is denied.

Though, because of the interface-based caching mechanism, if a client were to connect and invoke procedure A, the authorization would be cached by the RPC runtime. Therefore, if the client reuses the same binding to invoke B, the security callback is not invoked, and the request is served. This is exactly the type of behavior we need to exploit here.

There is still one thing to know though, which is not explicitly mentioned in the blog post. Whenever a client alters its binding, the server does not use the cache, so the security callback is invoked again.

Solving the maze

The ultimate goal was to generate the appropriate server-side state represented by the structure PLAYER_CONTEXT. More specifically, the flag bPlayerFound had to be set to 1, so that the procedure HsGetFlag could be invoked.

To do that, the idea was to solve a kind of maze, starting from the exit, and working your way out to the entry point as follows.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

1. "HsGetFlag" call requires:

- Impersonation Level = "IMPERSONATION"

- Authentication Level = "PRIVACY"

- Context->found = true

2. "HsGetFlag" authorization granted through:

- An RPC call with the opnum 42

3. "Context->found = true" requires:

- An RPC call to "HsSeekPlayer"

- Context->name = "Alice"

- Context->location = "Wonderland"

4. "Context->location = Wonderland" requires:

- An RPC call to "HsHidePlayer"

- An RPC call to "HsSeekPlayer"

5. "HsSeekPlayer" call requires:

- Impersonation level = "IDENTIFICATION"

- Authentication level = "PRIVACY"

6. "HsSeekPlayer" authorization granted through:

- An RPC call to "HsHidePlayer"

7. "Context->name = Alice" requires

- An RPC call to "HsCreatePlayer"

8. "HsCreatePlayer" authorization granted through:

- An RPC call to "HsCallReady"

9. "HsCallReady" call requires:

- Impersonation level = "IDENTIFICATION"

- Authentication level = "INTEGRITY"

From there, the exploit consisted in implementing all the steps in reverse order. The only thing to know here is that the impersonation and authentication levels could be set using the API RpcBindingSetAuthInfoEx(A/W). The authentication level is the third parameter. The impersonation level can be set through the structure RPC_SECURITY_QOS, which is passed as the last argument.

As for the check for the OpNum 42, the RPC interface has only 8 procedures, so there is obviously no procedure with the OpNum 42. Nevertheless, this value is also controlled by the client. Personally, I simply added non-existent procedure entries in my client-side IDL file such as long HsNotUsed8();, until I reached long HsNotUsed42();. This way the MIDL compiler generates all the stubs for you.

When trying to invoke the procedure HsNotUsed42 though, you just have to expect the client-side RPC runtime to throw an exception with the error code returned by the remote server. In that case, it would be 1745 - RPC_S_PROCNUM_OUT_OF_RANGE.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

__try {

// We need to call HsNotUsed42 to pass and cache the authorization, but

// the procedure number is not defined, an exception will be thrown. This

// is expected.

wprintf(L"[*] 5) IMPERSONATION + PRIVACY + HsNotUsed42() -> Authorization cached\r\n");

ret = HsNotUsed42(BindingHandle);

} __except (EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER) {

wprintf(L"[*] RPC runtime exception: %d - 0x%08x (this exception is expected).\r\n", RpcExceptionCode(), RpcExceptionCode());

}

And finally… Here is my exploit code in action!

Conclusion

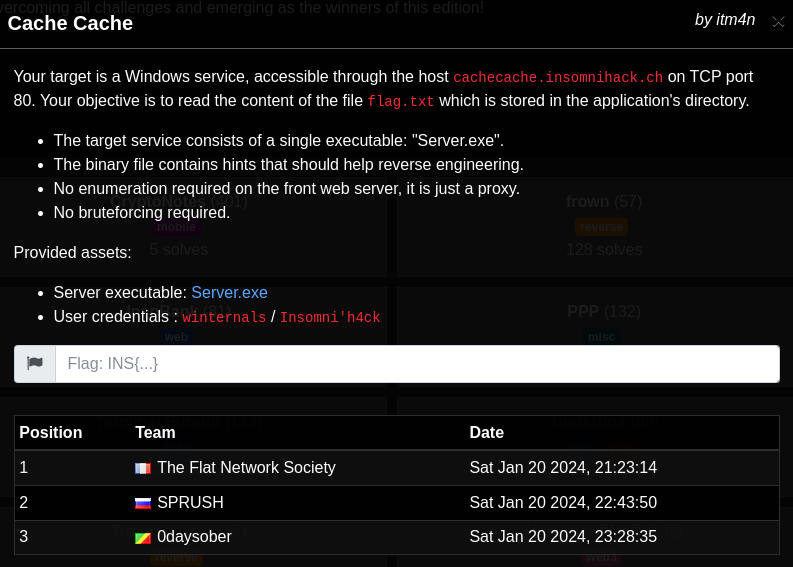

Last year, InsoBug was solved by only 3 teams. This year, Cache Cache was solved by a total of 8 teams. Congratulations to them! ![]()

First three teams who solved the challenge

First three teams who solved the challenge

This was supposed to be a hard challenge, and I’m glad so many people chose to grapple with it. Obviously, not all the players were able to reach the end, even after spending hours on it, which can be understandably frustrating, but that’s what you sign up for when you participate in CTFs I guess. ![]()

A last word about the challenge’s name. First, the word “Cache” was intended to hint towards the solution, as I mentioned earlier. Second, the name “Cache Cache” is French for “Hide-and-Seek”. Although French-speaking people were more likely to get the joke/pun, and the references in the procedures’ names, it was definitely not a requirement to solve the challenge. ![]()

Links & Resources

- Insomni’hack

https://www.insomnihack.ch/ - Insomni’hack 2023 CTF Teaser - InsoBug

https://itm4n.github.io/insomnihack-2023-insobug/ - Cold Hard Cache - Bypassing RPC Interface Security with Cache Abuse

https://www.akamai.com/blog/security-research/cold-hard-cache-bypassing-rpc-with-cache-abuse